Key Takeaways

- A corporate bond is a type of debt instrument issued by companies to raise money. When you invest in a corporate bond, the company uses the money to support its operations or fund special initiatives.

- Most corporate bonds pay interest periodically until the bond reaches its maturity date. The interest payments you receive are referred to as coupons.

- Corporate bonds get categorized based on their maturity term (short-term, intermediate-term or long-term) and the creditworthiness of the company issuing the bond (investment grade or non-investment grade).

- Generally, the longer the term, the higher the interest rate of the bond. Non-investment grade bonds usually have higher interest rates than investment grade bonds to compensate investors for a higher degree of risk.

What Are Corporate Bonds?

Corporate bonds are a type of debt security issued by companies as a way to raise funds to support operations, finance special projects, buy back stock or pay shareholder dividends. When you purchase a corporate bond, you become a bondholder until the bond reaches its maturity date.

Once the bond reaches its maturity date, the debt gets repaid to the bondholder in full. Maturity dates can be anywhere from a few years to over 10 years after the bond is issued. Before the bond reaches maturity, bondholders receive fixed-rate interest payments called coupons on the amount loaned, known as the par value. These coupons are paid about every six months until the bond reaches maturity, but the frequency can vary depending on the bond terms.

Some corporate bonds pay interest monthly, while others pay interest annually. Another type of corporate bond known as a zero-coupon bond pays no periodic interest at all. For zero-coupon bonds, the bondholder is compensated with a discount from the par value instead of interest payments.

Because corporate bonds are backed by companies instead of the U.S. Treasury or a government agency, they are known to have a higher degree of credit risk — but also the potential for higher returns.

There are many different types of corporate bonds. These bonds also carry more risk when compared to municipal bonds. Contact a financial professional to determine whether corporate bonds would be a good addition to your portfolio.

What Are the Different Types of Corporate Bonds?

Corporate bonds can be categorized according to the length of their maturity term, their credit quality or a combination of the two factors.

The maturity terms of a corporate bond can range from short-term (under three years) to intermediate-term (three to 10 years) to long-term (over 10 years).

As for credit quality, corporate bonds are classified as either investment grade or non-investment grade. The investment grade classification is given only to high-quality bonds with a minimal chance of default. In contrast, the non-investment grade category gets applied to speculative bonds with a much greater likelihood of default. These types of non-investment grade bonds are commonly referred to as high-yield or junk bonds.

Beyond just their maturity date and credit quality, corporate bonds can be categorized in additional ways. Below are the four main types of corporate bonds:

- Secured Bond

- A secured bond is backed by some sort of collateral, such as property, equipment or other assets, that are pledged by the issuer. If the issuer defaults on a secured bond, the bondholder has a legal right to foreclose on the collateral.

- Unsecured Bond

- An unsecured bond, also referred to as a debenture, is not backed by any collateral. If you hold an unsecured bond, you have a general claim on the issuer’s assets and cash flows. Your bond may be classified as either senior or junior, depending on its priority ranking in the event of a default.

- Convertible Bond

- A convertible bond can be converted into another type of financial security (usually common stock) in certain situations.

- Callable Bond

- A callable bond can be redeemed by the issuer before the bond reaches maturity. Generally, this happens when interest rates fall, and the issuer can save money by retiring a relatively expensive bond and replacing it with a new, lower-rate bond.

How Do Corporate Bond Ratings Work?

Whether a corporate bond gets classified as investment grade or non-investment grade comes down to the bond rating that gets assigned by credit rating agencies.

Bond ratings can have a huge impact on how investors feel about buying certain corporate bonds. Generally, lower-rated bonds offer higher yields than higher-rated bonds to compensate investors for the heightened credit risk.

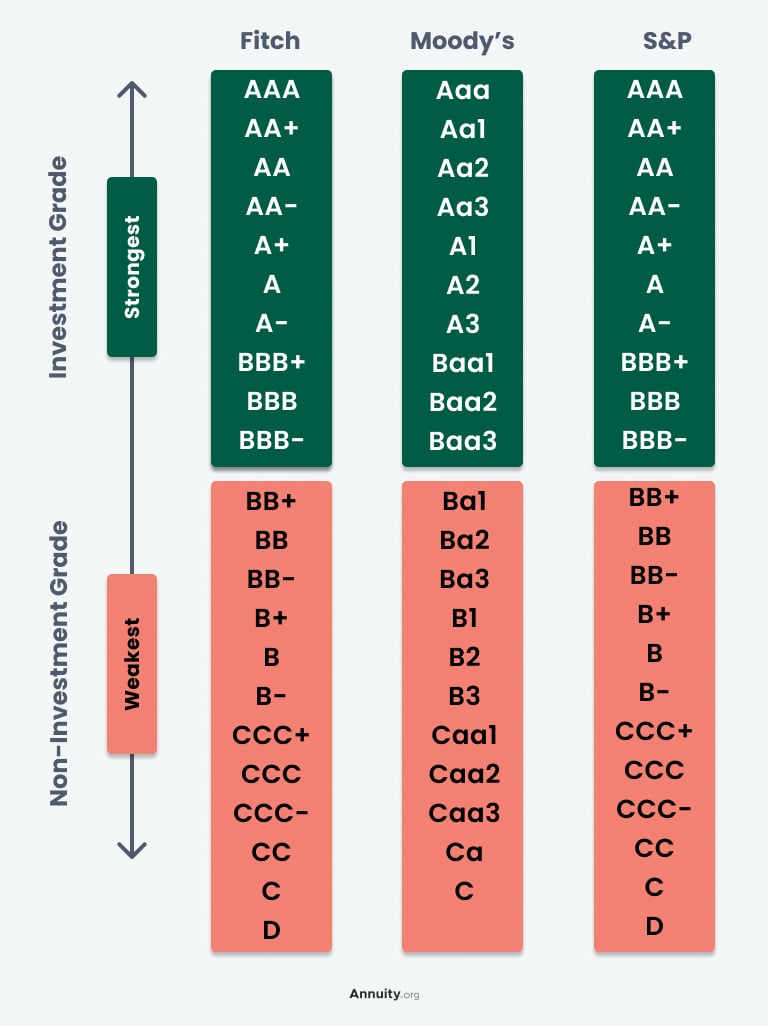

There are three main rating agencies (known as “the Big 3”) that assign ratings to bonds: Fitch, Moody’s and S&P Global.

Each rating agency has its own unique way of calculating creditworthiness, but the end goal is always the same: to give an idea of how likely it is that bondholders will receive their promised interest payments and have their loans repaid in full at maturity. Instead of a numerical rating, the agencies assign a series of letters and numbers to indicate a company’s rating.

The rating scales assigned by the Big 3 are illustrated below. Bonds with ratings between AAA and BBB- (on the Fitch and S&P scales) or between Aaa and Baa3 (on the Moody’s scale) are considered investment grade and offer the best chance of debts being repaid in full. Bonds with ratings between BB+ and D (on the Fitch and S&P scales) or between Ba1 and C (on the Moody’s scale) are considered non-investment grade and of greater risk to investors.

How Do You Invest in Corporate Bonds?

You can invest in corporate bonds via the primary market or the secondary market. In the primary market, companies issue debt directly to investors in exchange for cash.

The secondary market is where investors trade previously issued corporate bonds with each other. Trading in the secondary market is mostly done with the help of a financial advisor, or by making trades directly through a self-service brokerage account. When you trade bonds in the secondary market, you’re not limited to buying individual corporate bond issues.

In many cases, investors gain exposure to corporate bonds by investing in index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). These types of investment vehicles provide share-based ownership of a “basket” of corporate bonds, which then make periodic interest payments to shareholders.

What Are the Pros and Cons of Investing in Corporate Bonds?

Corporate bonds offer a relatively safe way to generate a consistent stream of income, as long as you keep in mind the quality of the bonds you’re buying. Some bond issues are illiquid and highly volatile, with a high degree of interest rate risk.

To decide if corporate bonds make sense for your personal finance situation, consider this list of pros and cons of corporate bonds:

Pros

- Generally safe and can help stabilize an investment portfolio with growth-oriented assets

- Offers a consistent stream of fixed income

- Usually very liquid if they are investment grade bonds

- Ample opportunity for diversification, given the variety of corporate bond issues available

Cons

- Potential exposure to credit risk, particularly with non-investment grade bonds

- Can be highly sensitive to interest rate changes

- In some cases, bond issues are illiquid and difficult to sell at a reasonable price

- Can be an inferior option for those with long investment horizons and the ability to endure stock market volatility

If you do decide to invest in corporate bonds, most of your holdings should be in liquid, investment-grade bonds with a moderate maturity term. Some non-investment grade and long-duration holdings can be beneficial, but only in moderation.

How Do Corporate Bonds Compare to Other Investments?

Compared to other types of investments, corporate bonds are most similar to other fixed-rate debt securities like municipal bonds, U.S. Treasury bonds and U.S. government agency bonds issued by Fannie Mae, Ginnie Mae and others. Like corporate bonds, these types of investments provide reliable sources of income with a relatively high degree of liquidity.

An exception is tax-exempt municipal bonds, which are exempt from federal income tax, as well as state and local income tax if you purchase the bond in the state where you live. Given this favorable tax treatment, tax-exempt municipal bonds generally pay lower interest rates than otherwise comparable corporate bonds.

But just because corporate bonds are similar to these other types of debt securities does not mean they are always as safe. When you invest in a corporate bond, you’re exposed to more credit risk, but you’re usually compensated for this risk with higher bond yields.

Are Corporate Bonds a Good Investment?

Regardless of the credit quality of the bond you select, corporate bonds are neither inherently good nor bad investments. Their suitability depends on your unique financial circumstances and your risk-return profile.

Generally, corporate bonds are a good investment if you’re an income-focused investor wanting to add a relatively stable asset to your investment portfolio. But if you consider yourself a growth-oriented investor with a long time horizon, corporate bonds can be a poor choice of investment. For you, the opportunity cost of not investing in higher-returning assets like stocks and real estate can outweigh any benefit.

That said, corporate bonds can make sense for investors with short-term or long-term horizons. In the right circumstances, corporate bonds can enhance the efficiency of your portfolio — adding income while reducing volatility. To get advice on your specific situation, you should always consult with a fiduciary financial advisor or your banking institution.

Frequently Asked Questions About Corporate Bonds

A bond default occurs when the borrower — in this case, the company — violates one or more terms in the bond agreement. The most common reason for default is when the company fails to make an on-time payment of interest or principal. When this happens, you (as the bondholder) have the right to seek legal action against the lender to mitigate your losses.

Generally, the interest rate on a corporate bond is set to reflect the rate paid by a U.S. Treasury bond with a similar term length, plus a premium to compensate the investor for any additional credit risk and illiquidity risk. That said, supply and demand imbalances can push a bond’s interest rate higher or lower than anticipated.

The interest payments you receive from a corporate bond are subject to local, state and federal income tax. No exemptions are permitted.

You can sell a corporate bond before it matures by trading on the secondary market, where investors trade previously issued financial securities with each other. The most common way to sell bonds on the secondary market is through a financial advisor or a brokerage firm.

Generally, the longer the maturity term of a bond, the higher the risk and return. Bonds with a longer maturity term are also more sensitive to changes in interest rates. As interest rates rise, a bond’s price will usually decrease if all else stays constant. As interest rates fall, a bond’s price will typically increase.

A corporate bond’s interest rate is set to keep pace with inflation and compensate investors with a payment that reflects their exposure to risk. If inflation remains flat, the value of the corporate bond will not fluctuate (if all else is held constant). But if inflation spikes, the value of the bond will decrease because the remaining coupon payments and principal will have less purchasing power.